[ Paper PDF ]

[ IEEE Xplore ]

[ Presentation ]

[ Google Scholar ]

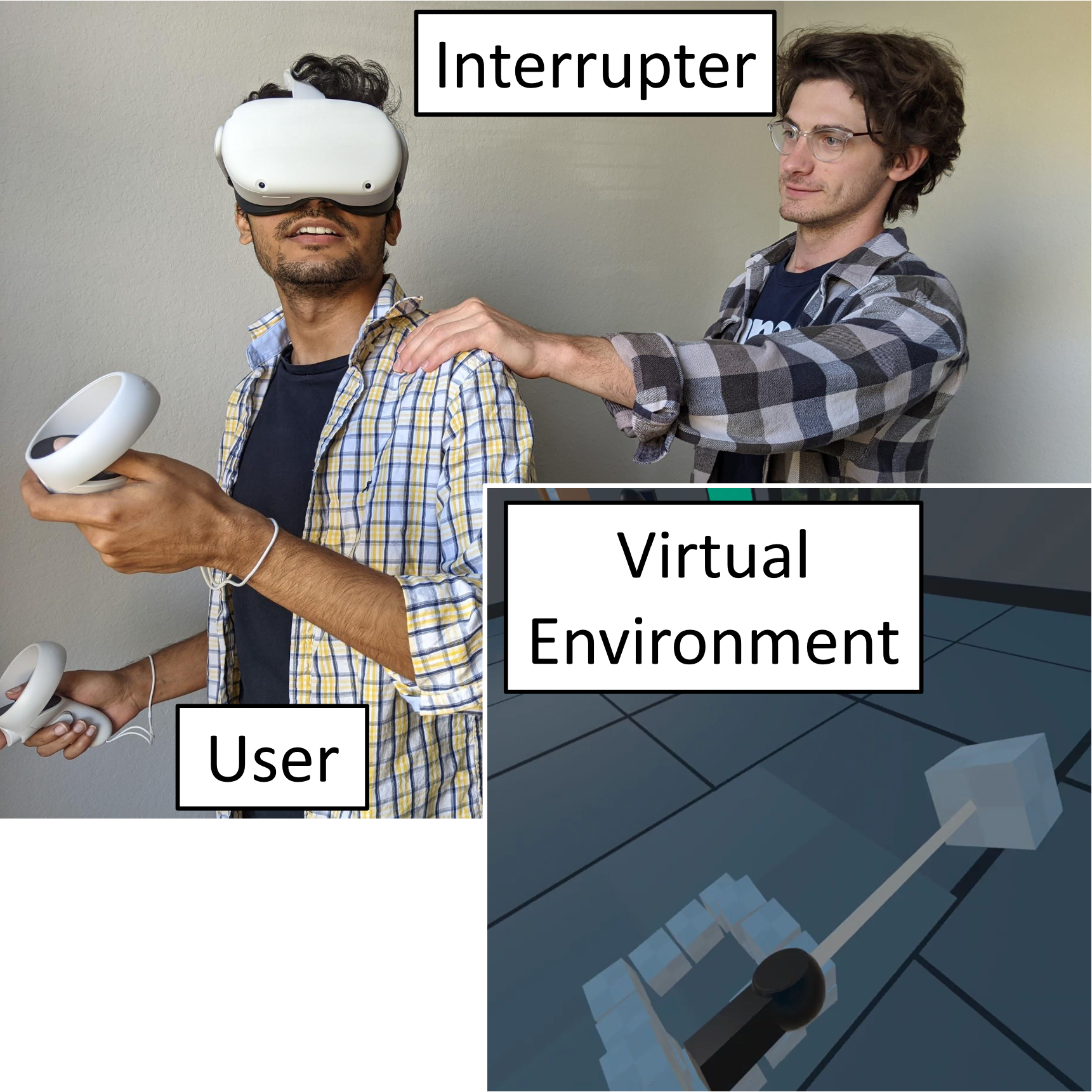

When someone puts on a virtual reality headset, they are completely isolated from their physical environment, including the people around them. This is by design—VR presents to be the most immersive computing technology. However, there are many cases in which a person wants or needs to interact with someone immersed in VR. Some examples, where "you" are wearing a VR head-mounted display:

- You are playing a VR game in your home, and your roommate needs to ask what kind of pizza you want.

- You are working on a 3D design task in VR, and your collaborator needs to tell you about a specification update.

- You are passing time on a plane in peaceful virtual environment, and your seat neighbor needs to move around you to use the onboard lavatory.

With the current state of the art, the interrupter cannot fully interact with the VR user unless they take off the headset. There is a lot of friction involved in that process, so it seems that there should be a communication channel that does not require the user to doff the headset. Additionally, the interruption is often jarring for the user. They are immersed in another world. When someone taps them on the shoulder or speaks to them, their physical environment abruptly calls them back. This process could be smoother.

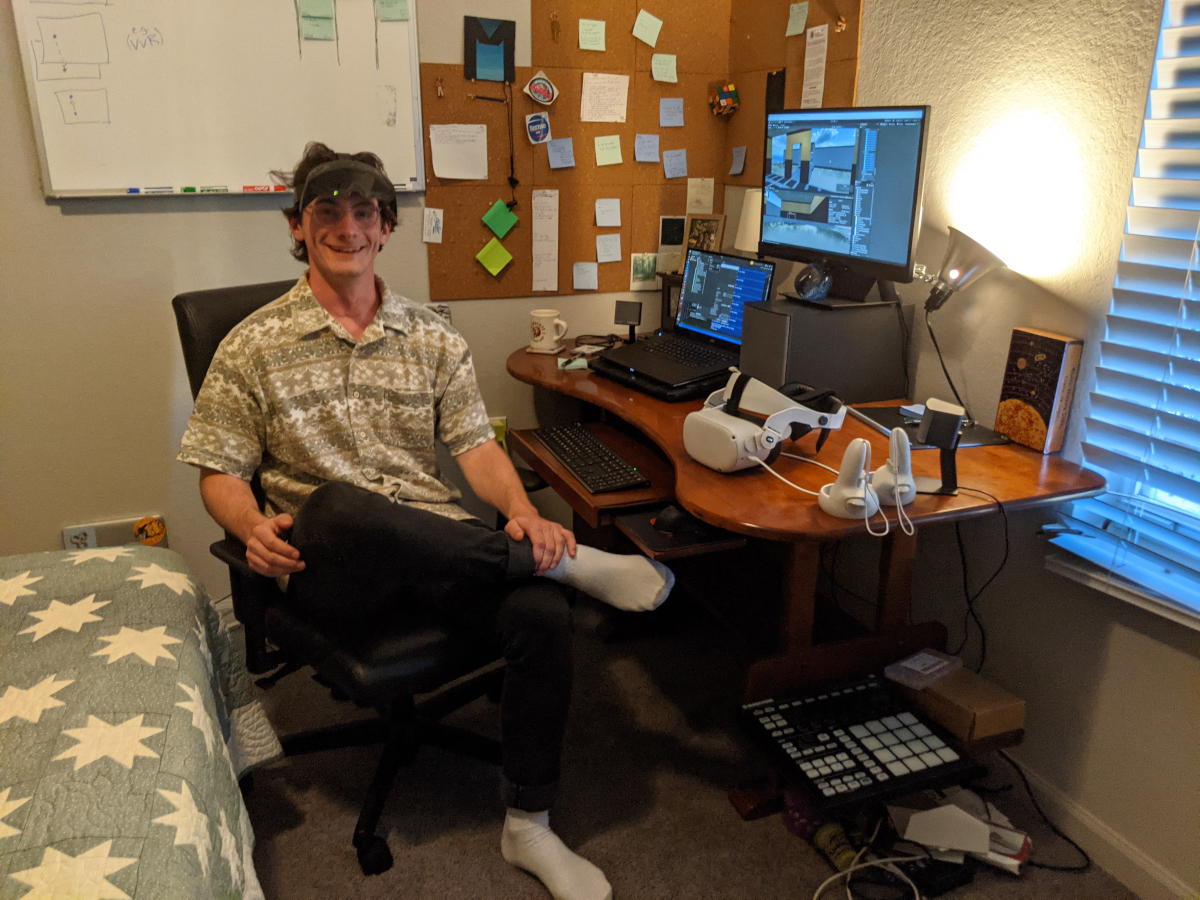

With the help of some awesome people in my lab, I designed, implemented, and ran an experimental design human subjects study to examine ways to facilitate this interaction. Our work was published in the proceedings of the International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR) in October 2021. You can read the full paper here: Diegetic Representations for Seamless Cross-Reality Interruptions.

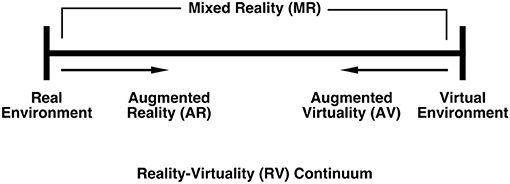

The word "diegetic" comes from describing narrative media elements. A story element is diegetic if it comes from within the context of the story world itself. For example, a sound in a movie is diegetic if it is produced by something in the scene (e.g., a radio playing a song). A different sound is non-diegetic if it is added to the scene as a narrative element (e.g., a musical score added to a scene where there is no orchestra plausibly nearby). I made a 2-minute creative explanation for this concept in my video presentation of this paper. You can watch the whole "live" presentation from that link if you want; my presentation starts around the 20:20 mark.

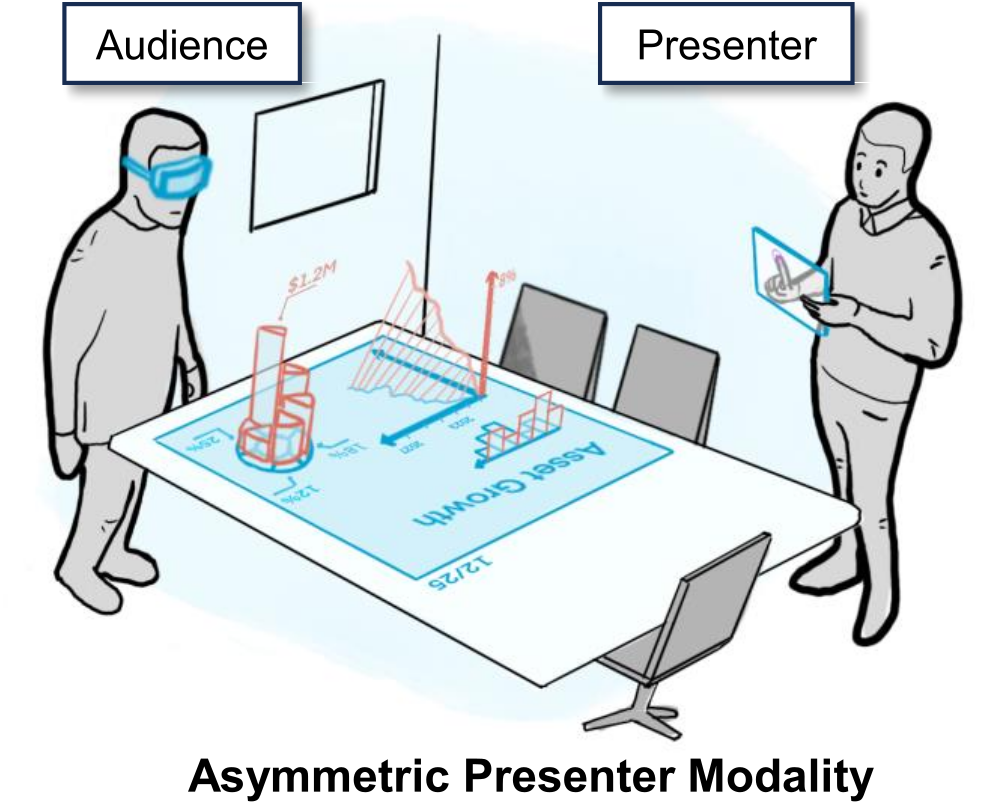

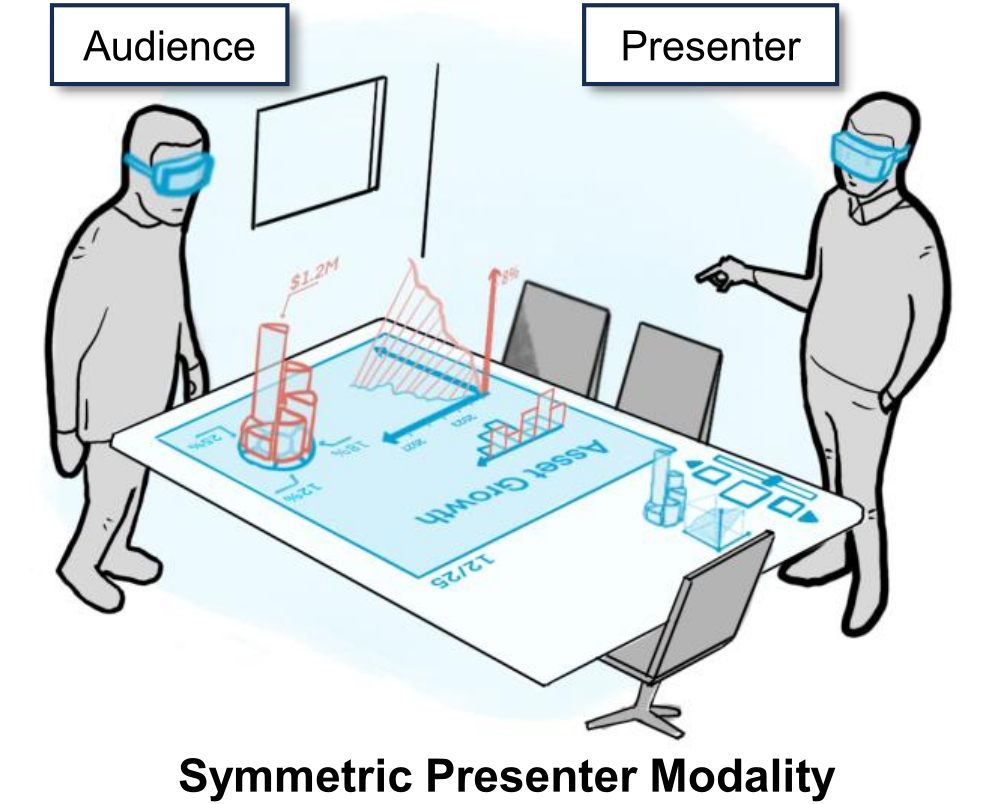

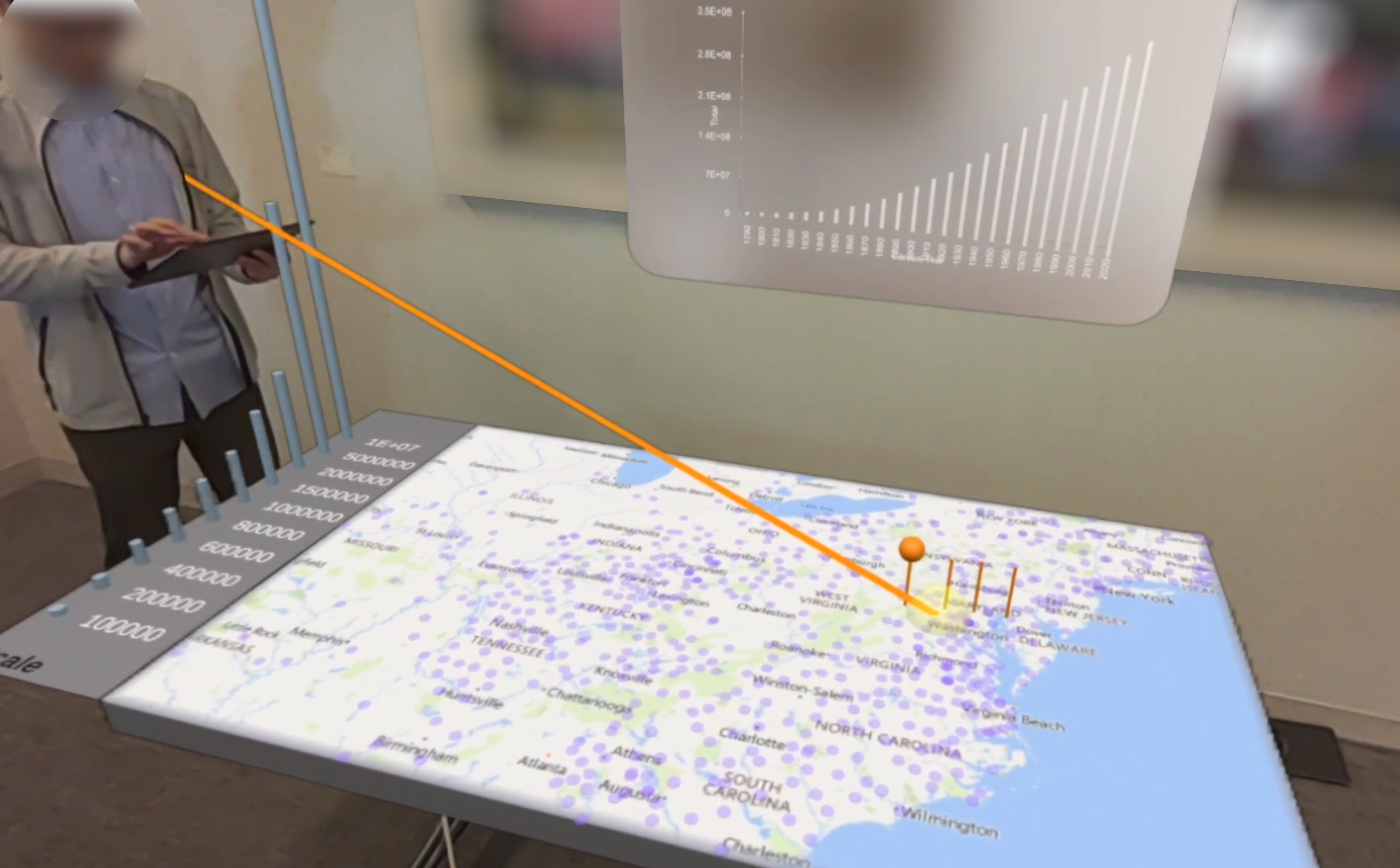

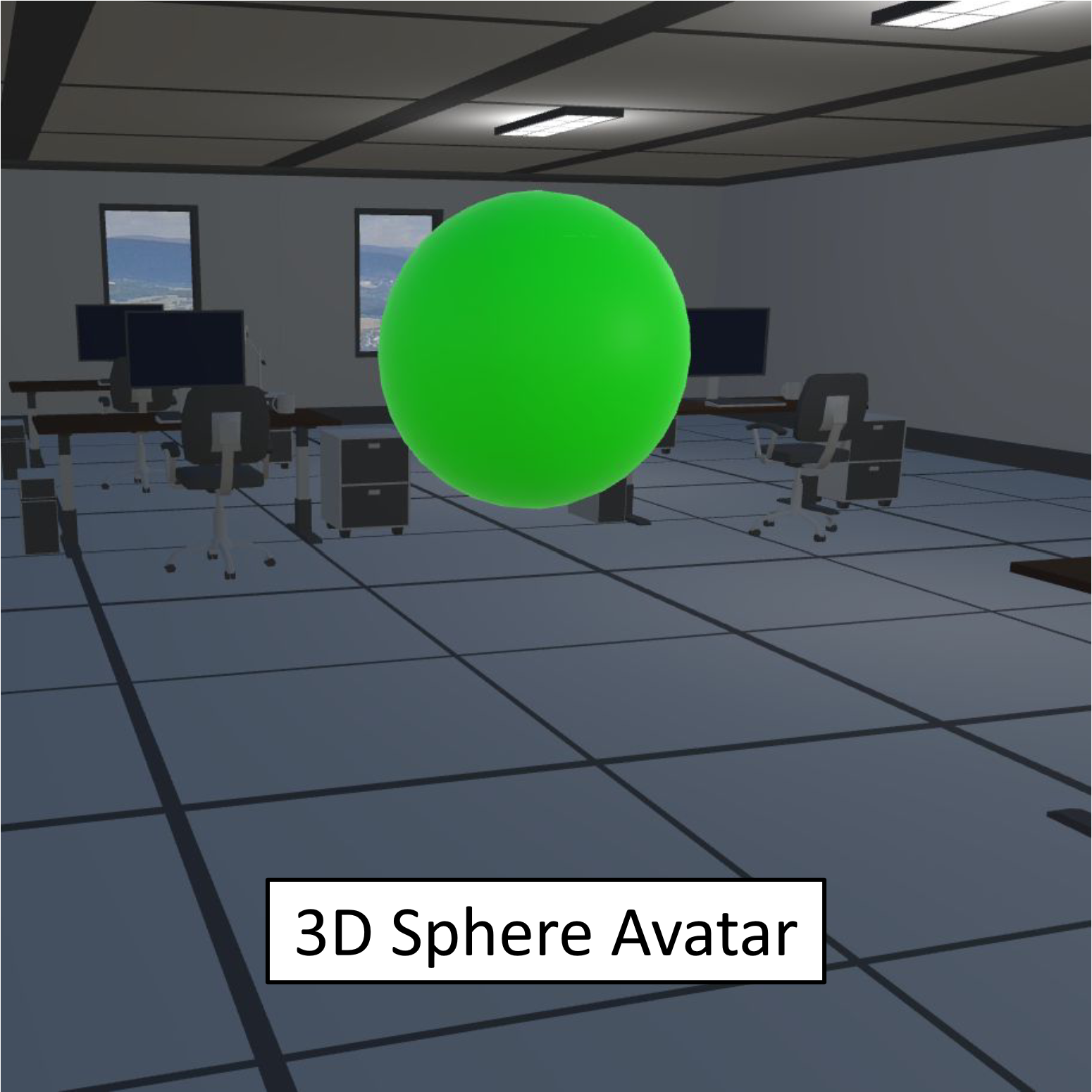

VR complicates the common definition diegetic because the virtual world completely surrounds the user. We can talk about audio mostly in the same diegetic dimensions, but the lines between diegetic and non-diegetic visuals blur a little. We explored how one might vary the diegetic degree of the appearance of an avatar to represent a non-VR interrupter to a VR user, and the different effects that might have on the VR user's virtual experience and cross-reality interaction experience.

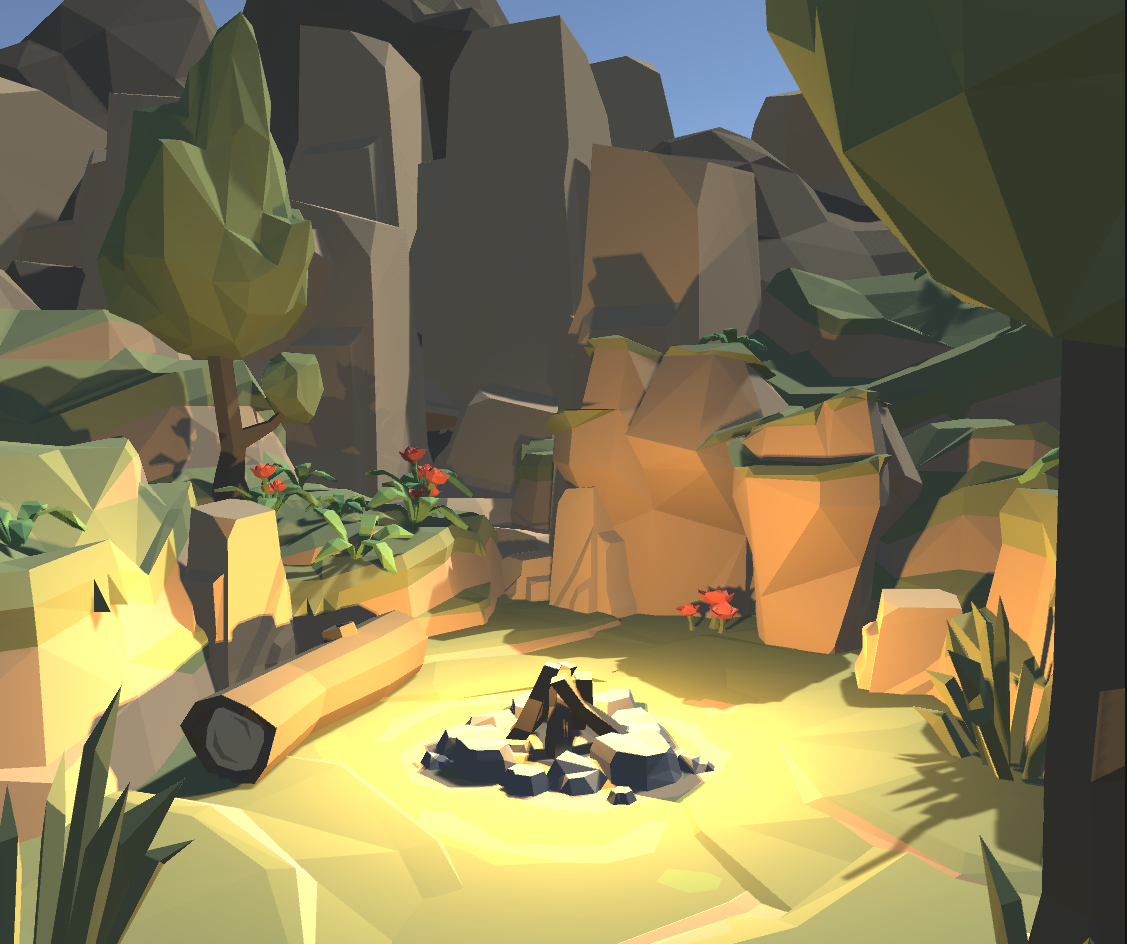

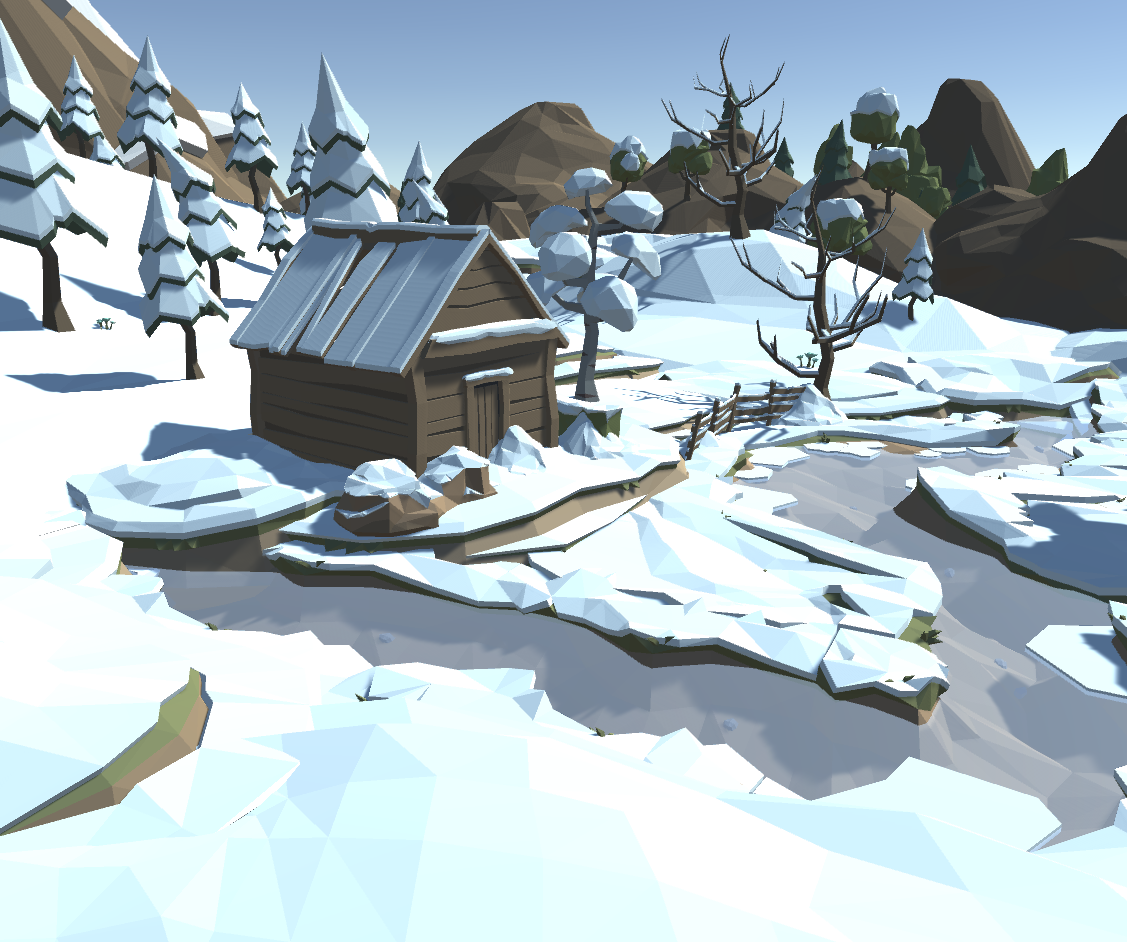

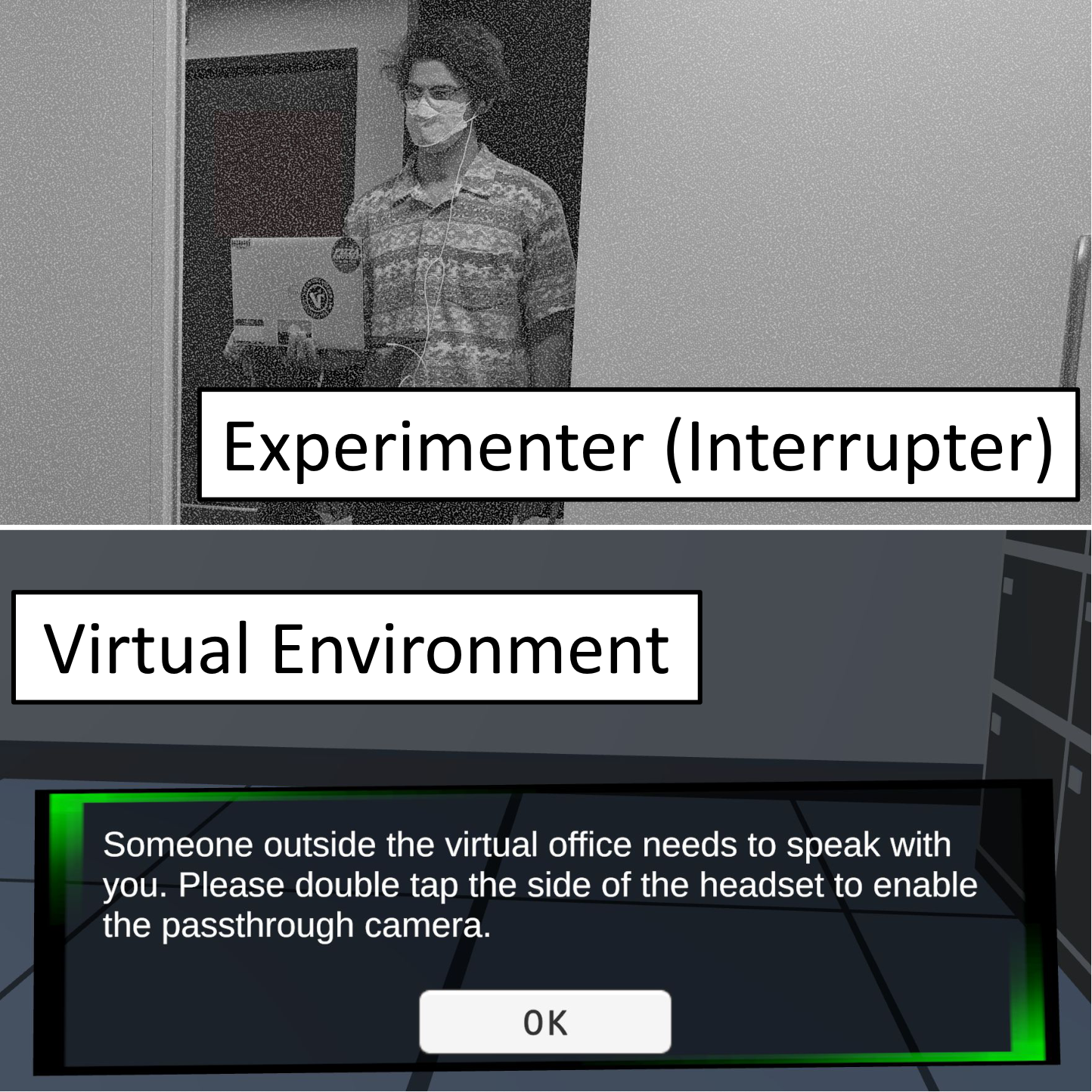

I built a virtual office environment and tasked participants with stacking virtual blocks in a couple different formations—just an easy task that could help them fall into a rhythm pretty quickly. The experimenter interrupted them part-way through each block formation. The way the interrupter was represented to the VR user changed each time:

- Baseline: interrupter taps the user on their shoulder, user takes off the headset to interact with interrupter.

- UI + passthrough view: UI notification alerted the user someone nearby wanted to speak with them, then the user activated the headset's passthrough view to see the interrupter through the headset's external cameras.

- Non-diegetic avatar: The interrupter was represented in the virtual environment as a floating green sphere.

- Partially diegetic avatar: The interrupter was represented in the virtual environment as an avatar in business clothes with a glowing green outline.

- Fully diegetic avatar: The interrupter was represented in the virtual environment as an avatar in business clothes.

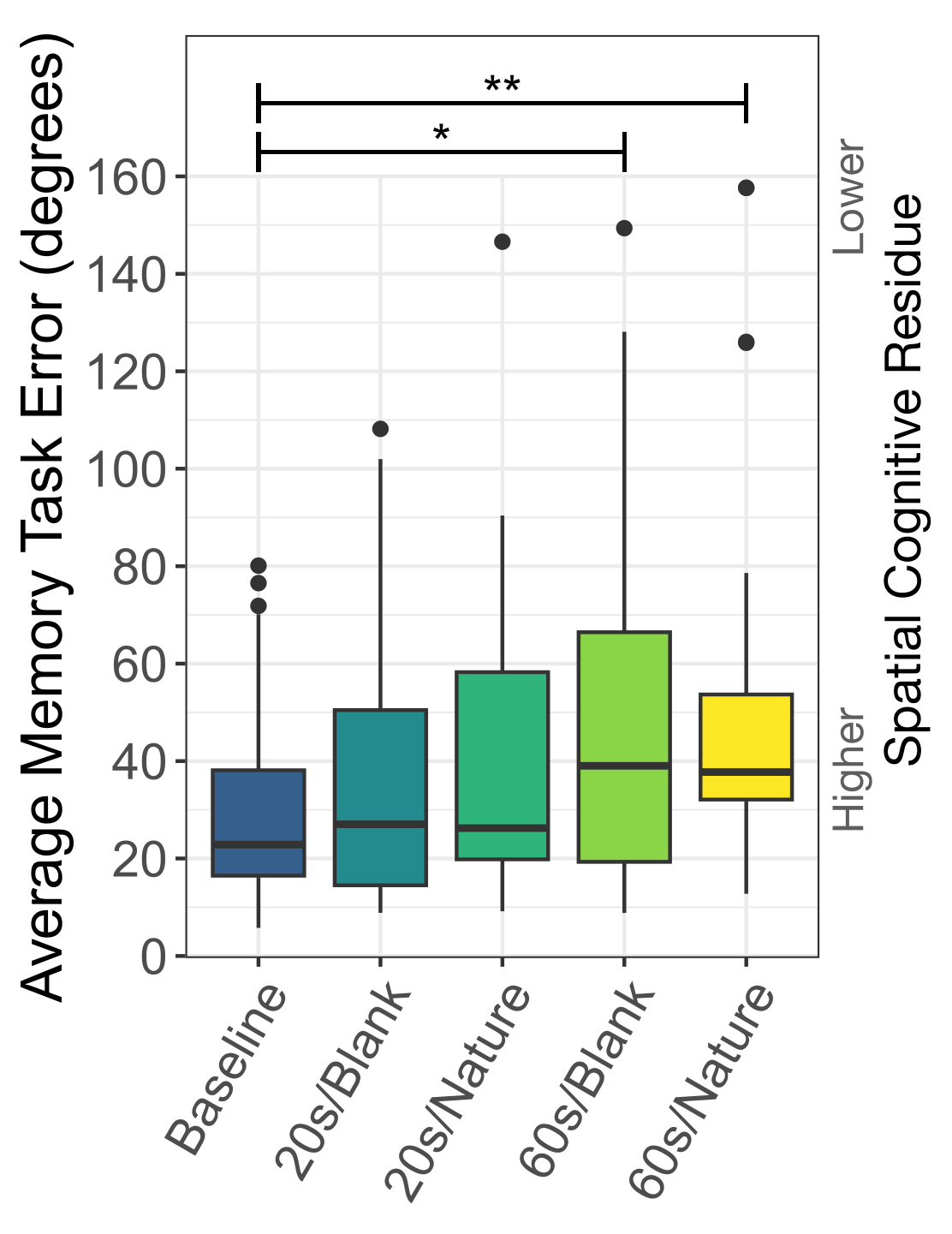

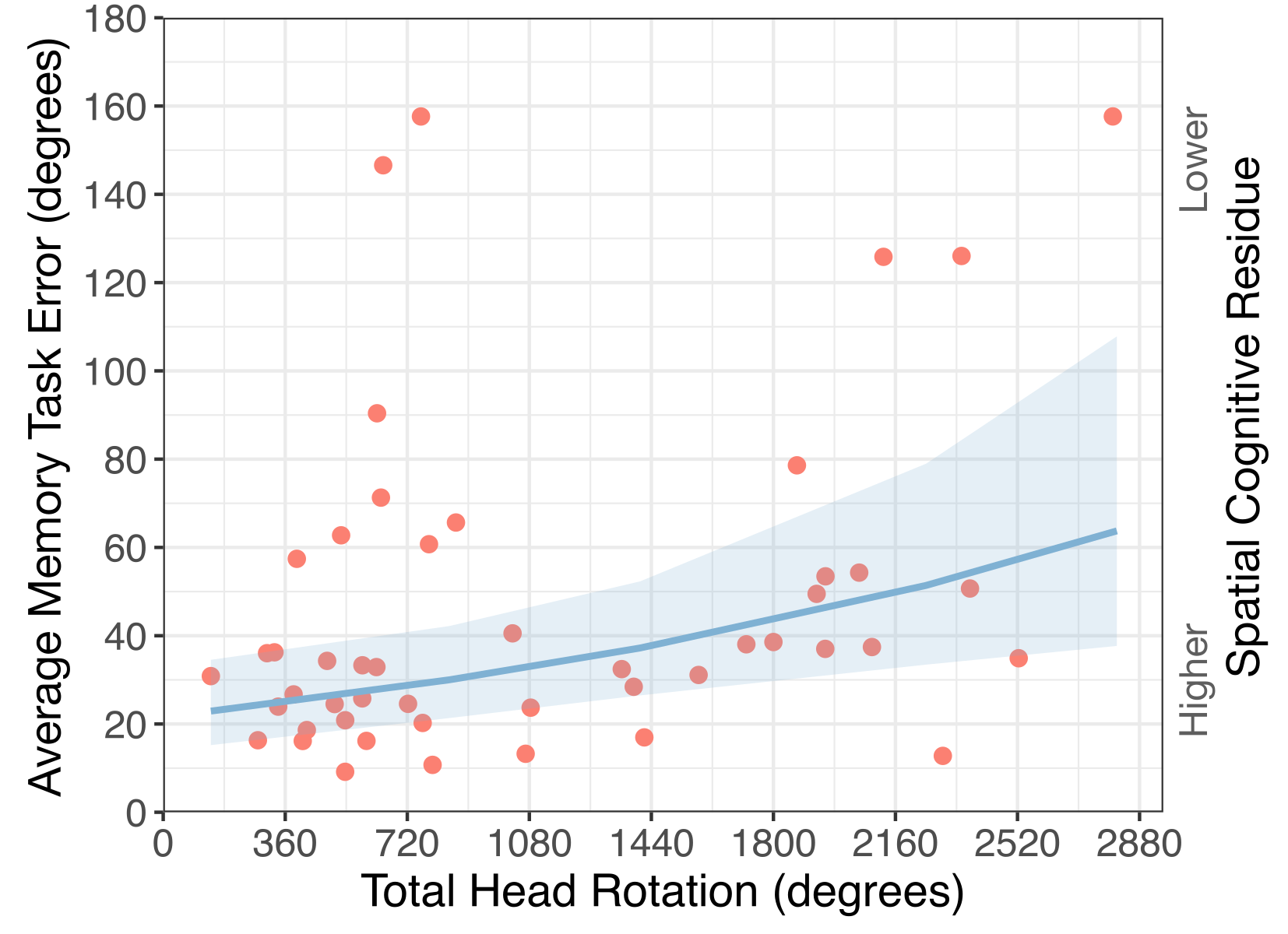

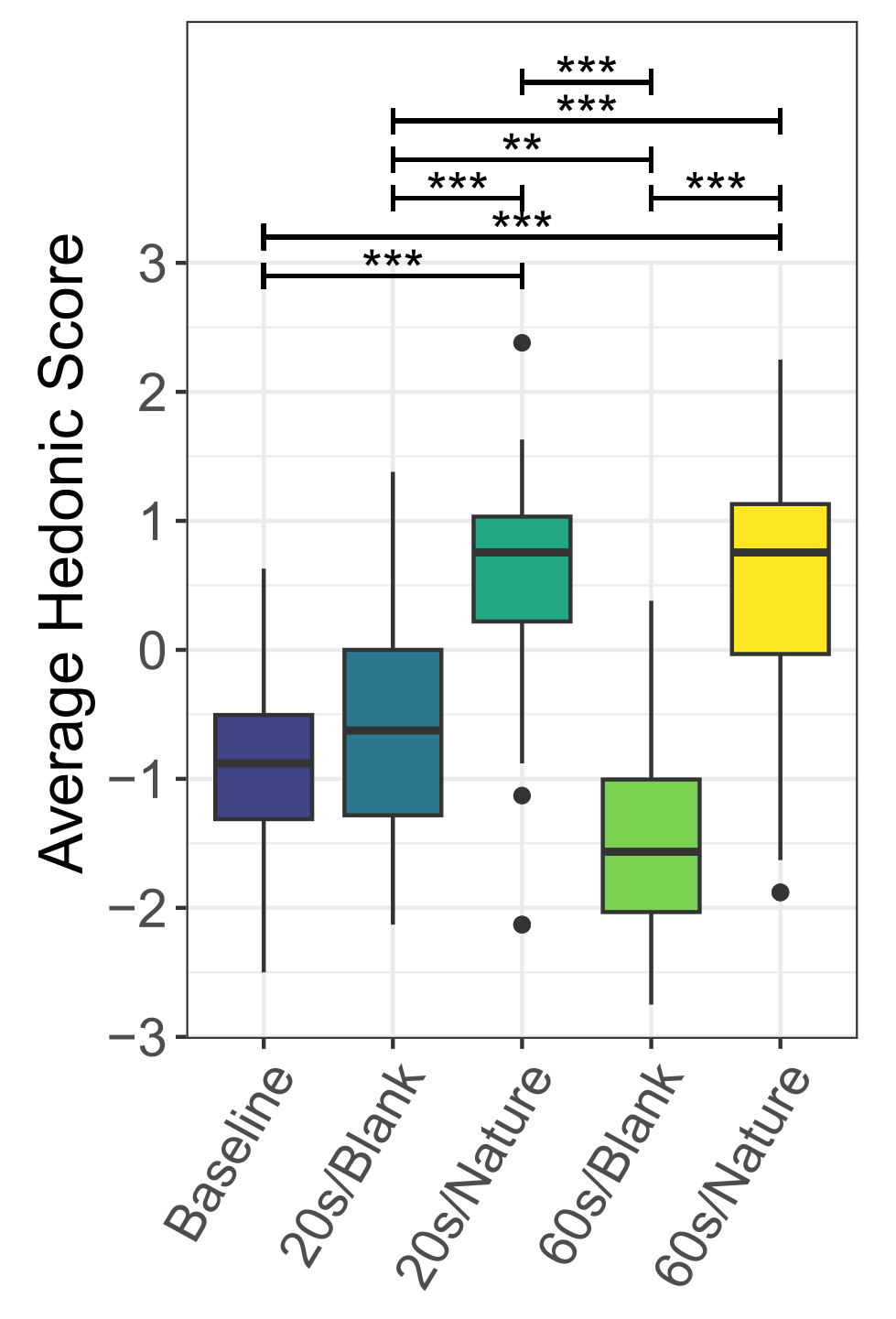

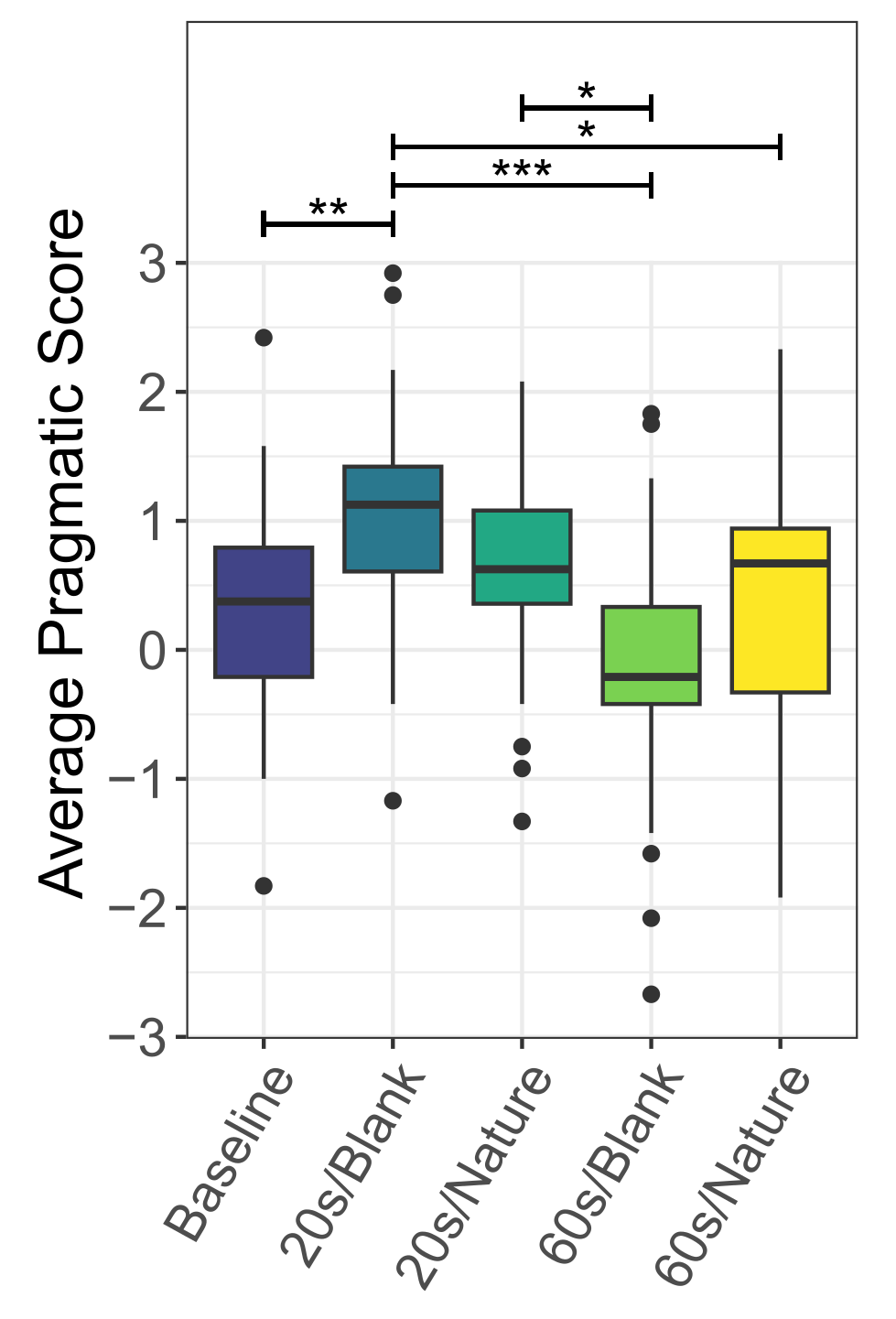

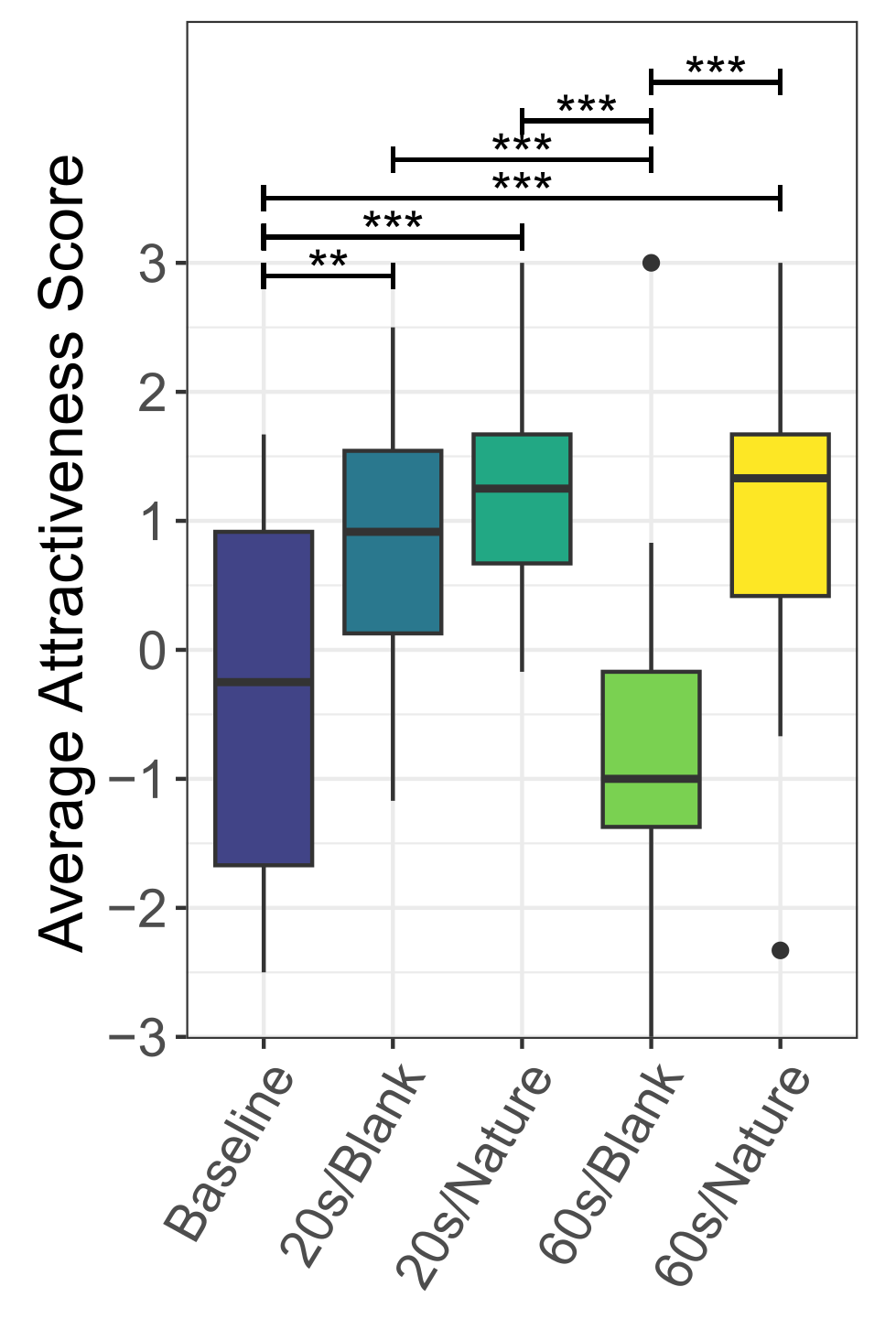

Based on a Cross-Reality Interaction Experience questionnaire we wrote, we found that participants rated the interaction experience with the interrupter highest for the partially and fully diegetic avatars. We also found that these avatars afforded a reasonably high sense of co-presence with the real-world interrupters, i.e., participants felt they were with a real person as opposed to a purely digital one. We found that participants more often preferred the partially diegetic representations. Their qualitative responses suggest why: several stated that the green outline helped them distinguish the avatar from the rest of the virtual environment; the outline suggested the avatar was not just an NPC (non-player character in a video game). I am interested in further exploring methods for representing cross-reality interactors, especially for interactions that may occur for longer periods (as opposed to brief interruptions).

Additionally, we asked participants about their place illusion, or their sense of "being there" in the virtual environment before, during, and after the interruptions. We found that the avatar conditions led participants to experience a consistent and high sense of place illusion throughout the interruption, where the conditions that caused participants to take the headset off led to a drop in place illusion that did not recover immediately after the interruption. I am interested in investigating further how VR users' senses of presence move and change throughout a VR experience.